Book launch: Max Dupain: A Portrait by Helen Ennis

Event video

Book launch – Max Dupain: A Portrait by Helen Ennis

Daniel Gleeson: Good evening, everyone. What a fantastic turnout tonight. This is just great. Well done, Helen. My name is Daniel Gleason, and I'm the Director of Community Engagement here at the National Library. It's my pleasure to welcome you all here tonight for this very special event. Before we begin, I would like to acknowledge that we are on Ngunnawal and Ngambri land, and I pay my respects to their elders, both past and present, and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people here today and online.

Tonight's event is a celebration of two great talents: Max Dupain, one of Australia's most influential and iconic photographers, and of course, Helen Ennis, a renowned photography curator, award-winning writer, fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities, and recipient of the J. Dudley Johnson Medal by the British Royal Photographic Society in 2021. Helen is currently, I always have trouble with this word, emeritus, thank you very much, professor at the ANU Centre for Art History and Art Theory.

Max Dupain was a major cultural figure in Australia. During a career that spanned over 50 years, he created countless images and artworks, many of which have become embedded in the nation's psyche and are seen as iconically Australian. One of the most well-known of these, of course, is the Sunbaker, which appears to depict a typical bronzed Aussie lying on a beach. I was really pleased to find out that Max took that photo at Culburra Beach, because I and my family have been holidaying there for over a decade. The locals call it Burradise. Max championed modern photography, and he was a leader in the field of visual arts in Australia. But, as Helen's book details, he was so much more than a brilliant photographer. This landmark biography reveals him as a complex and contradictory figure, who, despite his success, was filled with doubts and anxieties.

Helen's book also examines the sources of his creativity, literature, music, art, and his approaches to masculinity, love, the body, war, and nature. We are so pleased to be hosting this event, because the Library holds numerous Dupain images and several of his oral histories in our collection. And if you visit our Treasures Gallery, you will find some of Max's beautiful photographs on display that he took while here at the National Library.

Joining Helen tonight is the wonderful Alex Sloan. Alex needs no introduction. She's a popular Canberra identity and a fixture on ABC Radio Canberra programmes since 1995. It's my pleasure now to hand over to Helen Ennis and Alex Sloan.

Alex Sloan: Thank you. Thanks, thanks, Daniel. That'll make the ABC laugh, because of course I retired in 2017, but that also sent a few ruffles. Look, it's wonderful to see this turn turnout for Helen Ennis tonight. When I read Helen Ennis' biography of Olive Cotton, I thought to myself, "This is how biography should be done." And I was not surprised when the book went on to win many awards. This biography of Max Dupain is just as fine. And when I started reading the book, I sent Helen a message. I'm going to quote myself here. "I keep pausing to think about what you write and discover about him. You're not telling us, you're laying out what is known and then posing the best questions, considerations. So much to think about, and another layer of Australian history via this artist."

Helen Ennis' 'Max Dupain: A Portrait', is an extraordinary work of scholarship, extensively researched over many years, deftly handled, and beautifully written. I am so delighted to be sitting here with Helen Ennis tonight. Please give her that really fantastic Canberra welcome. Helen, congratulations. I can feel the love in the room, and I know you've got family here tonight. Your youngest grandchild Poppy is here. I know you want to thank some people right out of the box.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, so I'd like to welcome you all, of course, but especially friends of Max Dupain's and his family, some of whom will be watching online. But it's also a chance for me to just say how much other people have contributed to this book in so many different ways. And that includes my publisher, Catherine Milne, and the senior editor at Fourth Estate, Scott Forbes, because it really was a massive team effort, and the only reason that it's come to fruition is because of the contribution, ultimately, of so many other people. So I did want to say that it's important, but it is wonderful to have you all here. Thank you.

Alex Sloan: Was it the right order to write the biography of Olive Cotton before this one?

Helen Ennis: Look, I think it was. I had worked on Max Dupain a long time ago. I first met him 1982, very briefly, and then I interviewed him in 1991 for a show that we were curating at the National Gallery of Australia. It was going to be for his 80th birthday. And so I already knew Dupain, but I didn't know Olive Cotton's work as intimately, in a way. That had to grow over a long period of time, which it did. And to tell you the truth, I was much more interested in women's stories, because as a feminist biographer, I did Margaret Michaelis and then Olive Cotton. And the thing about the women's stories that's so typical is that there is such a lack of information. It's so thin.

And I think I was always of the opinion that Max Dupain had had so much attention, and when I was writing the Olive Cotton book, I had the sense of him being present at the table. Here was Olive, here was me, and here was Max Dupain. I was trying to focus on Olive, because she was so quiet, so reserved. And Max had always held a very public stage in Australia. And so I was saying, "Shh, shh, shh. I don't need the loudness of your voice, the insistence." But of course, I wrote the biography, because he does the most wonderful work, and there were so many questions to be answered. And those questions, over time, just became more and more insistent. And then, I thought, "There is no choice, but I will write that biography." And I was glad that Olive came first. I don't think otherwise that Max would've come up. It needed to be generated by those other kinds of forces.

Alex Sloan: And when I said this has been extensively researched, you already, I mean, clearly, by writing that first biography of Olive Cotton, you'd already done a lot of thinking about Max Dupain as well.

Helen Ennis: Yes, I had. And I think, in a way, I misjudged him, because what had happened in Australia, I think, because we have to remember that Max Dupain is an unusual photographer, because he had his commercial work all the time, and he had his artwork all the time. And so he had a public presence. He really just strode onto the stage in the 1930s. But why he was unusual is he wrote a lot. And if you go to the archives, you would be amazed at how many scribbled pages there are of his, writing about his work, but writing about photography, too, because he was a photography critic for many years, for the Sydney Morning Herald.

But the other reason that he's different from so many of our other photographers is his public profile. He made himself available to the media in the 1980s especially. And there just are so many newspaper clippings. Now, that was never the situation for Olive. There's a lack, and with him there's an excess. But yeah, it just meant that he is known to so many people. The photographs just feed into an image, not just of modern Australia, but of sort of personal connections, of going to the beach, for example, or seeing a modern building be built. He just taps so much into everyday people's experience.

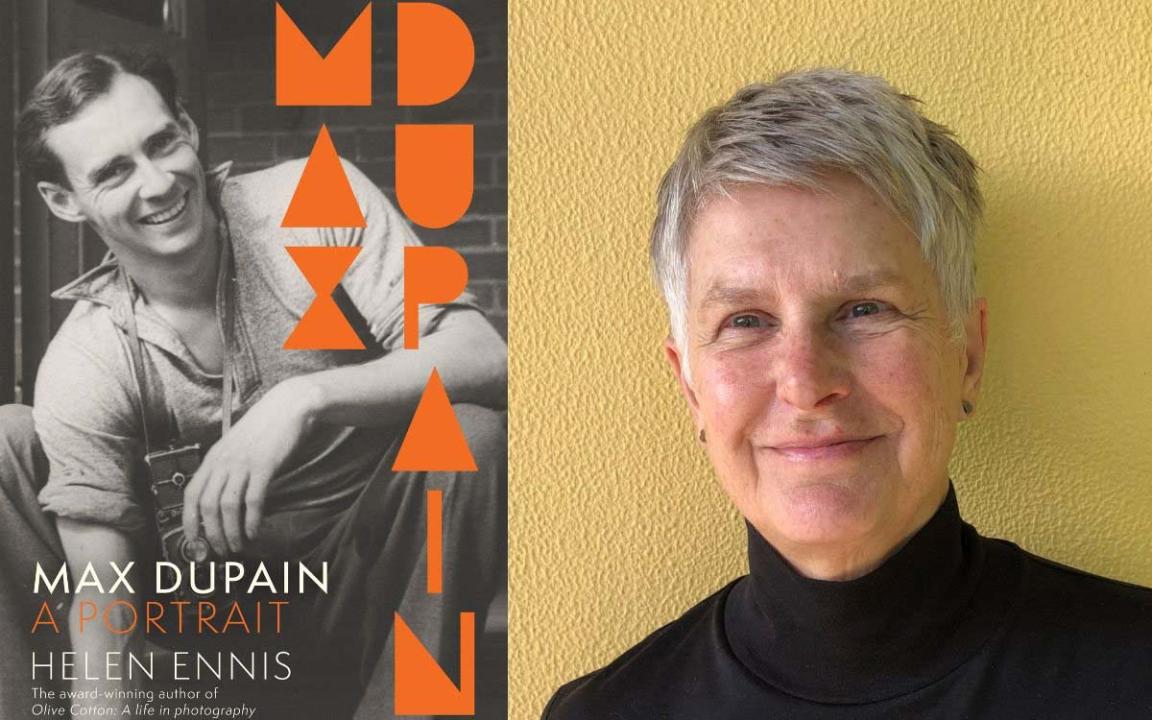

Alex Sloan: And the cover, I mean, this is just such, this is a very handsome, striking man, and you've chosen this cover. Just tell me about this.

Helen Ennis: So that photograph on the cover is by Olive Cotton, just before they were married. So taken 1939, he's holding a camera, but this is the pre-War Max Dupain, because as I said, I felt he had become one-dimensional. And my aim. There's a media theorist called Paul Virilio, it's the only bit of theory I'm going to mention, but he had this idea that, because we live in screen culture, everything has become thin. It's become flattened, like the screens that we're all used to.

And his idea was that reality has become like a fat man who feels that he has to apologise for being too fat. And that actually underpins a lot of my research, because I want to make everything I do fat. It's just absolutely necessary to have a lot of detail, many, many layers. And the Dupain book tries to do that. Here you have pre-War Max Dupain, who is so open to the world, so engaged, so invested in contemporary culture. And then, you'll see there are other portraits throughout the book, which take you in a different way on the journey, because the post-War Max is somebody very different, very affected by what's happened during the 1940s. And then the last phase of his life, he's someone different again. Yeah.

Alex Sloan: Many, many Maxes. I was interested too, before you described yourself as a feminist biographer. Tell me about that description and why you make that of yourself?

Helen Ennis: I feel it also underpins this book, because the first task is to bring forward the women in Max Dupain's life. And it's no accident that I chose a photograph of his mother in the kitchen, in her apron. She's busy drying out the dishes, because she was selfless. She was the one who made it possible for her son to do what he did, but also for her husband to do what he did. And there's a very poignant letter, I didn't use it in the biography, but it's from a friend of the mother's, saying she exhausted herself for her family, and we all know how common that is. So that was important for me, to bring forward women's experiences. And there, of course, women who absolutely have Max Dupain's back the whole way through, the mother, Olive Cotton, the second wife of Max Dupain's, Diana Illingworth, and then the studio manager, Jill White.

So those are key figures. He would not have been who he was, were it not for them. But of course, he was a product of a male-dominated society, who had all the advantages of being a man. And so all his mentors, all the ones who have the public acclamation, are all men, so Ure Smith being the first. So that's important to me. But I think it's about the context, different context, showing the home, showing society and culture more broadly. Those are all crucial, the different spaces, because we don't think of Dupain as being in the domestic sphere, and yet women are so crucial to the domestic modernist sphere.

Alex Sloan: And his second wife, Diana, you wanted her to be a bigger presence in this book. Tell me about that.

Helen Ennis: I did, because I think, in my view, the marriage between Olive Cotton and Max Dupain, which is so important for photography, because they have a very creative, mutually supportive partnership, is probably an exhausted relationship. And so when they marry, I mean, it doesn't appear to have been a marriage filled with passion. And Max Dupain is someone who was always looking for heroes. And we have to remember that number one hero, he tells us, interestingly, the heroes do not come from the visual arts, which is what you might think for a visually-oriented person, from music, it's Beethoven. Beethoven has the fusion of the mind and what he talks about, the heart, that it's music that hits you in the solar plexus.So Beethoven's number one.

But D.H. Lawrence is really important, too. And so he felt that feelings should come first. Now, that seems ironic, given how cool his photographs often are, but that's what I mean about one-dimensional, too. I wanted to be able to look at other photographs and different emotional registers, because he actually draws on a lot of other emotions that perhaps we haven't dealt with.

So to be a feminist biographer, also, I wanted an approach that was empathic, and generous, and compassionate, and that kind of thing. And Diana, to me, it seemed that she was a key in many ways that I couldn't get to. But when he falls in love with Diana, he is totally smitten, so all that.

Alex Sloan: You'll see the photo come up.

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: And what was not to love, really?

Helen Ennis: No, that's right. She was 19, he was nearly 30, but she just represented so much for him about everything he'd been reading and everything he hoped for, which is the stirring of feeling, and passion, and bypassing the intellect. That was really important to him, not to just get stuck on abstract knowledge. He wanted to live as a really passionate man and artist. It really drove him in that period of his life.

Alex Sloan: Max's daughter gave you great access and beautiful memories.

Helen Ennis: She did, yeah. So because Diana was so private and she felt that the emphasis should always be on the work and not on the family, she said very little on the public record, but Danina, who was Max and Diana's daughter, gave me wonderful memories. This is where, as a biographer, you always feel impoverished, because the kinds of sources that you get, and then you have the first-person testimony, it's always so charged and so brilliant. She, of course, Danina, talks about Max Dupain as, "Dad."

And so every time she said, "Dad," it just took me to a different place and space. "He grew amazing tomatoes, he loved azalea plants, he adored all sorts of animals and birds, and fed the birds," and so on, so those sorts of memories from her life. But of her mother, she said, how gracious, how social, and that's really important, because she was really gregarious, and everybody spoke about the kind of dignity and charm that she had.

Alex Sloan: So to Max, why and how did he come to embrace photography? Because he's described as devil driven. He needed to photograph like he needed to breathe, maniacal. Tell us about how he got there.

Helen Ennis: Well, I think it starts early. So he's an only child, and he's not in a family of privilege materially, but he is in a family of privilege in terms of a work ethic. And his father, who pioneered physical education in Australia, was a eugenicist. And they had a massive library at home, thousands of volumes. So he did have privilege in that sense, but he always felt a failure at school. Even in primary school, he felt bullied and hectored, and that he didn't fulfil the expectations of his teachers, and so on. So he definitely didn't feel academically comfortable. And when he graduated from Sydney Grammar, he said he'd learned only two things. One was rowing, because he adored rowing, and the other was English literature, and Shakespeare in particular.

So he was one of those kids who I think didn't fit in. And it goes back to D.H. Lawrence. You know, D.H. Lawrence always talks about how alone he felt, that he was always torn apart from the body of mankind. And I think Max Dupain felt very similarly to that. But photography, when he got it, and he's with Olive at this time, they're two kids, photographing together, she said it so perfectly. She said, "It's my medium. It's my medium for self-expression." And I think that, even though he doesn't say it that way, he felt similarly. And at school, he got a prize for the best productive use of spare time, and that was with photography. So it just, it was right for him.

But we've got to remember, culturally, in Australian society, I mean culture, everything was becoming more visual, of course, with the magazines were being produced and the ease of taking photographs. So he was at a rich moment for photography, and he excelled, yeah, straight away, and loved it with a passion. But some would say it was extreme. And that's those quotes, and Rosemary Bolton, Rosemary Dobson, our wonderful Australian poet, she knew him personally, and she used the word extreme, because she realised that it meant that if you had that kind of relationship with your work, where then did people fit in in that orbit? And that's why my first chapter is called 'The Three Worlds'.

Because his hypothesis, and he wrote it in his diary, his wartime diary in the 1940s, was, "There are three worlds," he says, "in a man's life. World number one is your family and your woman. World number two is your work." And world number three, he refers to it in a way that I think we can best understand is the kind of inner self, the emotional self. And he said, "Two of those worlds are untouchable and they're impenetrable to other people." So he was determined to keep those three separate. And it was a very flawed life philosophy. It didn't work. And that's why, as I said, about the different Max Dupain's, we can see the failure, in a way, of that kind of desire for extreme compartmentalization. It doesn't work.

Alex Sloan: In the book, you say there's a filmic image of Dupain which drove you to write this biography. Can you tell us about that? I think he's walking away, is that-

Helen Ennis: Yes, yeah. So because he was a modernist figure, he's left behind a massive archive, and it's estimated that, by his own estimation, a million photos. And so nobody can deal with that. That shows how excessive, how extreme his production was. But I felt he was slipping away in this one-dimensional way, sort of lionised, but almost stereotyped. And so I felt, before he went, that was the filmic image. I could see him in the clothing that he wore when I'd interviewed him and so on. I wanted him to stop, and turn back, and face not me, but us.

And it's interesting, because when my manuscript was read so wonderfully by amazing editors and proofreaders, I said, "He turned to face us." And three people said, "Don't you mean me?" But I didn't mean me, because we are his audience, and so it had to be us. I felt that he was turning back for us all to scrutinise, because the we is never homogeneous, anyway. You know, we're a complex, diverse society. But I wanted him to stop and turn back, yeah, and so that I could ask him the questions that were being generated from his work and from the research that I've done.

Alex Sloan: And this book, you do, you pose, it's full of questions, because I stopped with the maniacal, and, "He had to photograph like he had to breathe," but he was riddled with self-doubt.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, and that for me, initially, was the biggest thing. How can photographs that appear so certain, so black and white, not just in tones, but in the kind of vision that they espouse, how could they be so certain, so absolutist, and yet someone who made them be so, as he said in the '80s, full of self-doubt? And he says this in so many media interviews, "I'm racked with self-doubt, I'm consumed by it. I don't know. The only way I can smother it is by work," and so on. So he was telling us those things which I felt probably hadn't received attention at the time, but it was time now to see, was there some kind of reconciliation, or what's the relationship then between life and work and life and art?

And in his case, it's highly complex, because there's no simplistic things going on here. Picasso is the example I often use, that kind of really unfortunate biography, where there's a crisis in his life, and then it's represented in his paintings. Well, you don't see anything like that being played out in Dupain. So you have to think of another space then in which to operate, and then to ask these other questions. How does a boy who feels so unconfident, living in a society which doesn't value artists or the arts, become one of our greatest photographers? Like, how does that even happen? How does he form a life philosophy? Because he says every artist has got to have one. So how does he put his together? So there were just so many interesting questions. And then, of course, how does he age and what does he think by the end? Because as I say, that young Dupain is a very different man.

Alex Sloan: And I bet you're trying to answer those questions in your own head, as Helen poses them. And this is why I wrote to her, just reading this book, and this is the brilliance of it.

Helen Ennis: But I should say too, Alex, that for me, a lot of those questions don't have answers, either.

Alex Sloan: No, no, they don't.

Helen Ennis: And that's why the-

Alex Sloan: That's why I point to-

Helen Ennis: Yeah, that's right.

Alex Sloan: We're all trying to answer it, but no one has the answers to this.

Helen Ennis: No.

Alex Sloan: We talked about his relationship with women, but you write in the book he was uneasy and uncomfortable in the company of groups of men.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, yep. So that goes back to something I've already said about D.H. Lawrence. So Dupain is actually quite repelled, I think, the body of mankind. He finds his solace in the philosophies that come out of Norman Lindsay, of all people, and creative effort, because of this idea about the exalted few. Those who understand the value of an aesthetic life are part of a very small group. And he definitely saw himself as part of that group, as someone who was separated from others by that feeling, and yeah, so that he could never really identify with other people.

But one-on-one, like David Moore talks about his search for kindred souls, like-minded people. And it's a kind of desperate search in a way, because he finds very few of them in the world, and men generally really put him off. During the War, when he's a camouflage officer, you'd know probably that he was a pacifist, a really committed pacifist, and that was feminised in Australia, you know? Even the term camoufleur that applies to the people who learn how to do camouflage, and he was a camouflage photographer. The nickname was camo pansies. So he was very attuned to all those kinds of shifts, and he didn't find comfort, that's right, in big groups of men.

Alex Sloan: But his friendship with war photographer Damien Parer was absolutely revealing and crucial, wasn't it?

Helen Ennis: That's right. So one on one, so when he's in the studio, and you'll see a studio photograph come up, he said there were three graces, art, religion, and politics. And so this is another unusual aspect of our photographic history, because he really did debate a lot in that phase, a lot of contemporary politics, in a way, for example, that a lot of others might not have been so committed. Yeah, but Damien Parer, he adored, and the death of Damien Parer is one of those incidents that really shape his life.

I was going to say too that that search for like-minded souls, when he was in Cairns, and they're staying in a residence, all the pilots are there and soldiers, a whole lot of military people, he hears some classical music being played, and it sparked, and he traces through the residential quarters, and he comes to a room where there is a pilot playing classical music. And this pilot was travelling with a portable gramophone and his own selection of his favourite records. And Dupain is so thrilled to have found him, because he writes in his diary, "Gee whiz, he's got such and such by so-and-so and so-and-so," because Dupain himself was travelling with a portable gramophone and his own selection of classical music, of course Beethoven, was number one, and a whole swag of books, poetry books and that he was learning off by heart, some of the poems.

Alex Sloan: And when you said, you've got to understand Max Dupain in the pre-War and post-War, if we get to post-War and his work, I suppose with architecture, take us there to that.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, so that's quite right. I think that the pervasive image, if you're looking for a metaphor, after the War, is the phoenix. And again, there's a D.H. Lawrence poem, but the idea of the phoenix rising, because he said when he came back from the War, he was so discombobulated. That's not a word I use, but I love that word. He just felt completely at sea, as so many people did returning from just., he said the endless, the travel, being separated, of course, from loved ones, continuing to work, but not being able to really see the product of your work. So he was in a very unstable, uncertain place. And when he writes about it, his language is so raw and colloquial. It's almost confessional, I think.

And yeah, so he's got to work out, "Okay, what am I going to do with my life? What is even the use of art in a world where we've had war?" and so much of information about the Holocaust and that came out so late. So he's troubled, and yeah, what he manages to find is architectural photography. He had started early in the '30s, and some of his work had been reproduced. But it's because you've got a union, you've got the perfect buildings. He was always looking for divine form, a perfect work of art. And he could see that in some of the architecture that was being produced in Australia. And so it's a very sympathetic relationship, often, between the architect and him as the photographer, interpreting their vision.

And that goes for Harry Seidler initially, Penelope Seidler found the chequebook that had the first payment to Max Dupain in 1954. But all sorts of photographers just admired what Dupain was doing, the clarity then of his work, the precision, the cleanness of those architectural photographs. I think they're not rated highly enough still. And he knew that, he said people will always want photographs that have got people in them. And so he knew he couldn't live by selling his architectural photographs as works of art.

Alex Sloan: But it's a really important part of Australian history, and it's quite a male story too, isn't it?

Helen Ennis: It is, because he's working exclusively with male architects. That's right.

Alex Sloan: Yeah. Look, just because I know it's rattling along-

Helen Ennis: Got to blaze on.

Alex Sloan: ... and Daniel talked about Sunbaker, which I think Max, how did he describe it? He described it as just a curse, or what was his words?

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: An image with a heavy burden, distorting his career.

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: Your discussion, and you said you worked on that chapter a lot.

Helen Ennis: Yes.

Alex Sloan: Take us there, to that, an image. And I thought, "Oh, Helen's actually..." You know, I love this photo. This is just a superb photo. And I thought, ""Oh," but then I opened up, and I don't know if you've seen this, but.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, there it is. That's right.

Alex Sloan: There it is, there it is.

Helen Ennis: It's revealed.

Alex Sloan: So tell us, take us to this. Why was it a heavy burden for Max?

Helen Ennis: So that book design is by Sandy Cullen. Hasn't she done a brilliant job, choosing the orange and so on? So, but yeah, what Max Dupain said to me in 1991 was Sunbaked was a simple affair. He felt too much had been made of it. Because when you look at the original context, which we can do now, because the album in which the Sunbaker photographs first appeared is in the State Library of New South Wales. So there is an image in there, and it's tiny, you'll see it coming up here. It was an intimate image, it's a photograph made of a friend within a friendship group. But when Max Dupain's sort of second phase was starting in 1975, and there was going to be a big show at the Australian Centre for Photography, absolutely crucial show, that Graham Howe, who was the director there, he wanted Sunbaker. He knew it from that image being reproduced in a book, a monograph.

But Dupain said, "Oh, I lost that negative, but I do have another negative," which he'd rejected at the time. And as that negative that got printed, and that we know. So we know it as an exhibition print like this. So the original context for it have evaporated, but now we can go back and have a look. And just yesterday, Lisa Moore, who is David Moore's daughter, she wrote to me and she said, "Oh, would you like to know what Max Dupain wrote on the photograph of the Sunbaker, which he gave to David Moore?" So I had to sit on that overnight, because I didn't know if, having finished the book, like how I was going to handle that, and I said-

Alex Sloan: For the reprint, maybe.

Helen Ennis: That's right. I said, "Yes." And so she sent me the quote, and I asked if I could use it tonight. And she said, "Yes." And so what he'd written is, "Dear David, thanks basically for starting this off, but sometimes I wish we'd left those bloody prints in the cupboard." So here he is, still cursing this burdensome thing that he felt he was getting defined by it. And what I've tried to do in the book is build on all the wonderful scholarship and all the wonderful stuff that people have been writing about for many, many years, a lot of which is centred on Sunbaker, and just say, "Let's look at other things, too, and other perspectives." Because when you look at the beach imagery, and we've got to remember there's 250,000 negatives in the State Library of New South Wales that have been digitised, the beach is not as nearly as big as you think it might be. And images of sunbakers and images of single figures are not nearly as prolific as you think they might be.

You'll see a lot more of what I've got up there in the slides of masses of crowds and so on, and really delicate tracery of people lying on the beaches. And I think they're much more about beach democracy than heroic individualism. But you can have both views simultaneously. Yeah, they're not mutually exclusive, but we've got a bit stuck, I think, on one rather than the other. And yet, all that beach symmetry material, it's just got a perfect lineage in photographic history with Harold Cazneaux and other people, too. So I'm just trying to take the discussion of Sunbaker somewhere else, and to point out that that is a photograph that can be only taken by friends because, Sebastian Smee notices in the beach imagery, "Oh, Dupain is always behind the people," because of course, he's got the camera.

To be this close to someone is a predatory, and even, then you didn't have to get subjects' permission, but he's not comfortable doing that. He actually is far more comfortable, because he's someone who. One of his friends said, "He's a camera with arms and legs." He's not a gregarious person, he's not a people person, but his portraits are very fine, of artists and other creative individuals. He gets the like-minded soul portraits done beautifully. But yeah, so I'm trying to give a different perspective about the significance of the beach imagery in his overall career.

Alex Sloan: You're right, it's always meant much more to Dupain's audience than to him. And then, Sunbaker as an expression of the triumphalism and exclusivity of settler Australian culture, which denies Indigenous history, a lot has been kind of laid on this photo, hasn't it?

Helen Ennis: Yeah, it has. That's right. And for a long time, it was just worshipped , that it reflected sort of universal Australian experience. And so the critiques of it didn't come till later, where we recognised, oh, how exclusionary it is. But Dupain's landscapes, too, especially from really quite early on, they are the settler view of a landscape in which Indigenous people have no presence. But he was certainly very open to Indigenous culture, but not seeing Indigenous people as part of the modern world. He admired their closeness to nature and their lack of all the encumbrances of modernity. So we haven't really examined yet, I think, in all its complexity, how that fits in with other points of view.

Alex Sloan: And you said this chapter, which you really deeply thought about and wrote, you say it's a pivot about photographic history in this country.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, yeah.

Alex Sloan: Can you talk a bit more about that?

Helen Ennis: Yeah, so it's probably a chapter, to tell you the truth, that I don't like particularly, because it just had to do so much work, and I don't know if, for a reader. Because my approach to biography is forensic, in that it's nonfiction. I don't do creative nonfiction, where I speculate on what the day was like or anything like that. It's all based on evidence. I'm not making anything up. But I'm trying to, with my biographical approach, use all the conventions of fiction to try and develop my people as characters, to have a narrative momentum and so on. So that's a chapter that isn't very satisfactory to me, because of where it sits in relation to my approach to biography, because I'm trying to use ideas about empathy, and complicity, and that, too. So I thought it might be rather dull, sort of spinning its wheels a bit to get on. But that doesn't really answer your question, so.

Alex Sloan: Well, let me just take you, and I really want to get this story in, the role of curator is really important for Max Dupain and Gael Newton's work was crucial. You quote a great story about the exhibition curated by Gael, and her shock once the pictures were hung. And so she went into a panic and started sweeping, tell us that story.

Helen Ennis: Yes, that's right. So Gael worked very, very closely with Dupain in the late 1970s for this retrospective exhibition that was held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1980. And yeah, she'd hung the show, and he was coming in, and she was feeling anxious. But when she saw them up, she thought, "Oh, it's all about sex," that there's a really strong sexual thing happening, a kind of binary between male and female, and so on.

She thought that when he came in, he would see that, and that the reviewers and so on would see that the question she is posing is, "Was he a classical sexist or a sexy classicist?" And so she is still working on that. I mean, this is the thing about Dupain, he is rich enough, and complex enough, and contradictory enough that he has given a lot of people a lot of material. Yeah, so we're still asking, I think, lots of questions about that.

Alex Sloan: But hilariously, when he came up the stairs and Gael was sort of sweating on the showing this is just pulsating with sexual tension, he just didn't notice at all.

Helen Ennis: No, he didn't. That's right. No, he didn't. But I would have to say he is a fantastic photographer of women, and I do think that the photographs he's taken of nudes have not been fully understood yet, because we see them as being objectified and so on. But he worked with women who really wanted to be photographed, and there's three people in particular, Olive Cotton, who posed for him, but especially Jean Lorraine and then Moira Claux, who really used the photograph much more performatively. And yeah, so I think you have to give them credit for that, that they're trying to really challenge the status quo, that Australia is so conservative at that time. And Dupain, now steeped in especially European modernism, and mad about Man Ray is wanting a whole vocabulary of eroticism to change the way you live in the world.

Alex Sloan: And he did tell Olive Cotton that he felt he had to be in love with the woman that he was photographing.

Helen Ennis: That's right.

Alex Sloan: Yeah.

Helen Ennis: Yeah. He said jokingly, that's right.

Alex Sloan: But how do you think, you know, in terms of the photographs that he's produced, that was quite a truthful moment?

Helen Ennis: Well, yes. I don't know for sure, because again, he's someone, as I say, who puts the camera between him and the world, and so what is he really thinking? But he did take very fine glamour portraits. He was exceptional at that in the 1930s and right through.

Alex Sloan: There's going to be an exhibition of his work, and Man Ray, is that right? Can you talk a bit about.

Helen Ennis: I probably can't talk about that one.

Alex Sloan: But just the influence of-

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: Yeah,.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, Man Ray. That's right. And there is going to be a big show at the State Library of New South Wales the year after next, which has now been announced. But yeah, so Man Ray is an enormous discovery. He's just a young man, 24. [unclear] Smith says, "Hey, why don't you review this incredible book of Man Ray photographs?" and it is an incredible book, and he's just completely blown away.

But interesting, you see, when we talk about that philosophy of life, it's not just Man Ray as a photographer, it's Man Ray as a man, and an artist, and his iconoclastic attitude, because he says, "Let's kick the status quo up the arse." That's how Dupain sees Man Ray. He uses all that sort of bawdy language and that to try and challenge good taste, and politeness, and so on. And his nude photography is coming under some of that, too, really trying to, for those who were looking at it, just push their buttons, like really challenge conventions.

Alex Sloan: Llewellyn Powers, is that how I say his name?

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: Dupain quotes him, but in fact he's misquoted him.

Helen Ennis: That's right.

Alex Sloan:

Tell us that story, and his devotion to his writing, and.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, so we're in the final phase of Max Dupain's life, when he has become quite melancholic. And he says that his Bible, because Norman Lindsay helps him decide that he is anti-Christian, that he wants to be an artist, that Beethoven is number one, that the classics are super important, and so on. So he's got all that, but at the same time, he's discovering Llewellyn Powers and this book, 'Compassion Clay'. And he said to me, "Oh, you should get a copy," which I did. It's just a little book.

But he carried it around, in the sense he said it was his Bible. He kept them with them, right through his life. But Llewellyn Powers is a much more formidable figure, in fact than Norman Lindsay. And Max Dupain says, "Norman Lindsay, I'm not interested in this visual work. It's what he writes." But his writing is so crazy, and in a way, Llewellyn Powers is so much more coherent and so much more poetic, but the, "Nothing matters," so what Dupain kept saying later in life is, "Nothing matters." And he said that to me, too. And then I realised in all the media interviews, "Nothing matters, nothing matters"

Alex Sloan: "And nothing remains."

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: It's very nihilistic, isn't it?

Helen Ennis: That's right, really nihilistic. But the difference is that Llewellyn Powers, he thinks something matters. And he says it's the senses and the apprehension of the world through the senses. And Dupain actually does quote that, too. He says, "The senses, the senses, the senses," they are the counter to that nihilism. But yeah, so there's a Roman gravestone, and Llewellyn Powers ends his book with it, but Dupain misquotes what's on there, doesn't he? I can't remember exactly what he says.

Alex Sloan: Well, he just said, "Yeah, nothing matters and nothing remains," but it goes on to be actually quite hopeful.

Helen Ennis: That's right, that's right.

Alex Sloan: But he'd chosen the kind of nihilistic or the nihilistic, which yeah, again, makes you feel so sad about the last part of his life.

Helen Ennis: I know, because he said, "Look, if a person doesn't have their work," someone like him, he said, "What do I do? Grow mushrooms?" He just really felt defeated by what had happened, because his business partnership had broken up, he was becoming ill. And for someone interested in Vitalist philosophy, who worships youth and beauty, the ageing body and the ageing processes, it's not something to look forward to.

And he couldn't get out into the landscape. He found it too hard to walk, he had a sore foot. And one of his friends said jokingly, "Oh, you should just get your foot cut off, and then you'll be all right." And of course, his response was. He was so appalled and so melancholic. Nothing by this point was a laughing matter, but he did keep photographing. And you will see that with the last photograph by him in the book, I think he still, every now and then, especially in the flower studies, achieves something really, really wonderful.

Alex Sloan: And just before I hand over to questions and our lovely National Library team will come with a microphone, so if you have a question. His whole narrative is about being a victim and about not being able to just create the work he wants to create. But I think you point out his public persona is of the hero?

Helen Ennis: Yeah, so I think that's right. The way he was approached is definitely as a hero, and all the obituaries talk about that. And there's even one comment that he is Australia. There's so much conflation, and that is so unfair to him, because even though he is totally committed to Australia, he loves it, he said he has such a short umbilical cord, he just is so enamoured of Australia, his last photographs are not about Australia. They're about Nature, with a capital N.

And this is another key thing in the book, that he becomes a universalist, not a nationalist. And that's through William Blake, his 1983 exhibition. That's who he quotes. So again, drawing on literature. But yeah, coming to see the land and the things that will endure, that nature will be triumphant. Humanity won't. He thinks we're puny. And look, we are. I mean, if you think of the state of the world now and what he had gone through in the War in the 40s, yeah.

Alex Sloan: And so how do you want us, if you say, come back and look at us in that film, what would you like us to kind of read from this and from this story?

Helen Ennis: I think I'd probably go back to the statement from Diana Dupain, who lived with him for 47 years, and she just used the phrase, "Complex and contradictory." I think I'd like us all to give him the respect which allows for all his triumphs, but all his vulnerabilities, and his failings and that as well, to humanise him, and not to heroisize him. And yeah, to give the work these sort of multiple contexts. But to see him as someone who was very, very human, and not just this symbol of everything that was great in Australia and the sort of triumph of masculinism, because I don't think he's that at all.

Alex Sloan: It was a lot laid on him. Now, put your hand up and we'll make sure we get some questions in. Yes, thanks. Raise the light. Who'd like to ask a question? I can keep going forever, but I'd love you to get your questions in, which our lovely staff is standing by with a microphone. Anyone got, oh, good on you.

Helen Ennis: And there's one there, here too.

Alex Sloan: Oh, great. Fantastic. Oh, thank you.

Audience member 1: Thanks, Helen.

Helen Ennis: Pleasure.

Audience member 1: It's a three-pointed question. I don't know much about Max Dupain, really, but thanks for enlightening me tonight. Did he do much in colour? That's point one. Point two, he was prolific with, as you said, over a million-odd photos. What percentage of those do you think he actually didn't like? And the third one was he was obviously a man of the moment of his era. How do you think he would've found the modern era, with iPhone photography and the prolific amount of photography, compared to his quality?

Helen Ennis: Thank you. No, they're all great questions. So colour, he really wasn't for colour. He felt that black and white allowed something that was much more creative, in fact. We have to remember that he comes out of that heroic phase, too, of black and white photography. So being in the dark room was something that he prized enormously, as did Olive Cotton. So the printing was so important. He felt colour was too literal, and it just didn't leave enough room for creative imagination, either his or the viewers. So that's why he was very dismissive of colour. And that then put him at odds, of course, in the 1980s, when colour becomes something that a lot of contemporary artists were very keen to explore.

And the sadness about that, in a way, is that Dupain, the pre-War Dupain, who's so associated with the vanguard and progressiveness, then becomes a champion of status quo and the establishment, because he doesn't like colour and he doesn't like fabricated photography. He feels it's a real bastardization of photography itself. So that's one.

And yeah, the prolific thing, now, that's really illuminating, because I've looked at so many things online, in person and so on, and it's quite clear to me that there were moments when his photography was really premeditated and he didn't use a lot of film. And architecturally, he would often work out beforehand what was going to happen. And those works really came out of a very considered approach. But other times, he was shooting a lot more negatives, waiting for something to happen. You see them at the beach. There's so many that are unruly, because he's just waiting for people to get into the right space. And he talks often about luck, the role of luck for him and his photography, that he needs to work with luck to sort of energise and animate.

Alex Sloan: The Meat Queue, The Meat Queue-

Helen Ennis: Yeah.

Alex Sloan: ... which was his favourite photograph, wasn't it?

Helen Ennis: That's right. Yeah, The Meat Queue. Exactly, that's what he nominates as his best photograph, because he said, "There they all are." And then a dame, he calls her a dame, breaks the queue, and everyone, you know, it just introduces a restless kind of energy. So that, for him, was important.

But look, the percentage, what he said was, I think for us, the commercial Dupain and the art Dupain are both really important, because they both define modern Australia. But for him, he actually did make a distinction himself, and it comes from John Sikorski, who was the director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. So Dupain says, "I am a mercenary during the week, I am my true self on the weekends," because that's when he is taking his own photographs. So I think that he wasn't enthusiastic about a lot of the stuff that he did. And he reflects himself, he says, like product advertising, the dance photography, a lot of portraiture, a lot of that, he dismisses. He really does downplay it. He's not happy with it.

Now, the third question.

Alex Sloan: Was about iPhoto, you know, taking on the phones.

Helen Ennis: Yeah, I think because Max Dupain's credo, and Danina stressed this, was in all things and life as well as in art, keep it simple. And he says that such a lot. So he didn't like complicated equipment. And Michael Nicholson, the architectural photographer, he told a story about working in the studio with Max, and he still. You will have seen there was a line, like a washing line hanging in the studio, and the prints are all clipped up on there.

And Michael bought a print drying machine and plugged it in, thinking, "This will save Max Dupain such a lot of time." And he said, "Can you get that thing out of here? It's too noisy." But really, what Michael stressed was that he didn't want fancy equipment. He didn't want photographers talking about technique. He said he wanted them to talk about the Moonlight Sonata. That was his thing. And so he preferred not to mix with photographers, but to mix with other creative individuals.

Alex Sloan: Great. We've got a question here, and then we'll.

Audience member 2: Thanks, Helen. That was a wonderful talk. I do apologise, my question is actually about Olive Cotton.

Helen Ennis: That's okay. She's a big part of the story, too.

Audience member 2: Yes. In one of her school books, you mentioned that she writes a quote, a stanza, actually, "One crowded hour of glorious life is worth an age without a name." That appears throughout the canon of Australian war photographers. Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett writes it in a pamphlet advertising his films.

Helen Ennis: Oh, wow.

Audience member 2: Neil Davis writes it in the front of every single one of his diaries. David Brill has it inside his jacket. What is it that ties Olive Cotton to this series of Australian war photographers? I have no doubt that this was a phrase that she would've said to Damien Parer at some point in their relationship.

Helen Ennis: Oh, no, that's a very interesting question, and I don't have an answer, but that's right. I mean, Damien Parer, that may well have been part of their understanding. So no, I mean, I can relate it to Dupain and this idea that the passion. You don't want to be ordinary. You know, you want a life that is inflamed with high-order energy, and yeah, is a sort of pivot for change and so on. So Olive would not have known many of those photographers, but yeah, she's part of her time as well. So the resonance is that's really interesting, what it would've meant for her and what it would've meant for them. I think you'll need to explore it and write an article. I'd love to read it, thank you very much.

Alex Sloan: That's a great question. I think we've got time just for one more and then. Oh, just here. Thank you. Sorry if you didn't get your question in.

Audience member 3: Thank you so much, Helen, for such an amazing conversation this evening. I don't really have a question, but I thought that this could be something for you to speak to maybe further, the relationship between Dupain's psyche and the photographic medium, moving maybe more into the theory kind of chat. But do you think that Dupain's desire to control and maintain the difference or perceive his life in different spheres, and photography as a means to fix or create a sense of external certainty, where he felt internally that there may not have been any? And so you used the example of Picasso earlier on, and how Picasso was trying to externalise like the internal chaos, whereas could we read Dupain's work as his desire to fix and create form to the things that he struggled with inside?

Helen Ennis: Yes, yes, yes. I reckon that's a great point. And I think that that idea about fixity and certainty, in fact, that's in my last chapter, that's more or less what I'm raising, that he sort of makes a choice with his photographs to give us things that are very certain and are very absolutist, that are not about contingency and provisionality. And that's why I've spent the book, in a way, trying to find those other things, because they are equally really part of himself. But he was in an era when everybody had high hopes for modernization and modernity. You know, the whole modernist project, and he was a champion of that. But because he was a pacifist and there were more wars, and that yearning that he has for purity, and simplicity, and so on, it's not fulfilled. It doesn't come to pass.

And so I could even use a quote where when he is asked about why. Because he says, "I don't like people." He's quite frank about that, there's quite a few public statements. He said, "Going into a room of people, sure, I can do it, but it's a chore for me. And afterwards, I just think, 'What was the bloody use of that?'" So what he says is that he's not about being, he's about doing. And so I think what photography and that idea about fixity, it's giving him a project of action, because he's always got to be photographing, and he's always got to be printing, and then all the activities that come from that. So I think that is a really, really interesting and very relevant point. Yeah.

Alex Sloan: Thank you so.

Helen Ennis: And I don't psychologize it particularly, but I reckon you could.

Alex Sloan: You're going to love this book, you're just going to love it. I think, just at seven o'clock. Helen will be signing books and you can ask her many more questions. And I always say the alternative to bringing wine is to bring a great book. So you need to buy multiple copies of this book. Your friends and loved ones will thank you for it. But Helen, an absolute joy to be in conversation. Congratulations.

Helen Ennis: Thank you.

Alex Sloan: Thank you.

Helen Ennis: Thank you.

Daniel Gleeson: Thank you so much, Helen and Alex, for that discussion, which was just fabulous. And thank you to the audience for those amazing questions as well, based on huge knowledge, they're incredible. Upstairs, yes, we have the bookshop open. You can purchase some copies of the book, and I'm sure if you ask nicely, Helen will sign those for you as well. Now, if you can't get enough of Helen's work, in more good news, she's been working with the National Library's publishing team on two upcoming titles for our Artists of the National Library Series on the work of two other renowned photographers, of course, Olive Cotton and Wolfgang Sievers.

Helen will also be speaking at an event hosted by the Friends of the National Library on Tuesday 8th April next year, and sharing some of her favourite images by those artists. So please keep an eye on the National Library website in the New Year for those details. Or, you could join the Friends of the National Library, and you'll be kept up to date with everything that's happening at the Library. You can grab a brochure from the table on your way out on the right. So please now, invite you to make your way upstairs after one more round of applause for Helen Ennis and Alex Sloan.

Following the discussion in the Theatre, Helen Ennis was available for book signings in the Foyer.

About Max Dupain: A Portrait

From multi-award-winning writer Helen Ennis comes the first ever biography of the photographer Max Dupain, the most influential Australian photographer of the 20th century and creator of many iconic images that have passed into our national imagination.

Max Dupain (1911-1992) was a major cultural figure in Australia who was at the forefront of the visual arts in a career spanning more than fifty years. During this time he produced a number of images now regarded as iconic. He championed modern photography and a distinctive Australian approach.

However, to date, Dupain has been seen mostly in one-dimensional, limited and limiting terms – as exceptional, as super masculine, as an Australian hero. But this landmark biography approaches him as a complex and contradictory figure who, despite the apparent certitude of his photographic style, was filled with self-doubt and anxiety. Dupain was a Romantic and a rationalist and struggled with the intensity of his emotions and reactions. He wanted simplicity in his art and life but found it difficult to attain. He never wanted to be ordinary.

Examining the sources of his creativity – literature, art, music – alongside his approach to masculinity, love, the body, war and nature, Max Dupain: A Portrait reveals a driven artist, one whose relationship to his work has been described as 'ferocious' and 'painful to watch'.

"[he] needed to photograph like he needed to breathe. It was part of him. It gave him his drive and force in life."

About Helen Ennis

Helen Ennis writes on Australian photography and her latest book, Max Dupain: A Portrait (2024), is her third biography. Helen is Emeritus Professor, Australian National University, where she was Director of the Centre for Art History and Art Theory from 2014 to 2018. She was formerly trained as a curator at the National Gallery of Australia where she headed the Department of Photography from 1985 to 1992 and has worked extensively as a freelance curator, including for the National Library of Australia.

Her numerous publications include Intersections: Photography, history and the National Library of Australia, Reveries: Photography and Mortality, Photography and Australia, and award-winning biographies of Margaret Michaelis and Olive Cotton. Helen is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities and in 2021 was awarded the J Dudley Johnson Medal by the British Royal Photographic Society for her contribution to the history of photography.

About Alex Sloan

Alex Sloan AM has been a journalist for over 30 years, including as a long-time broadcaster with the ABC. In 2017 Alex was named Canberra Citizen of the Year. She was made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2019 for her significant service to the community and to the broadcast media as a radio presenter. Alex is deputy chair of The Australia Institute and a director of The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.